Last year in December, 2024 I had the pleasure of speaking via Zoom to the third-year creative writing class at Bennington College in Vermont, in the United States, about The Eternal Audience Of One. At the time, I was in a hotel room in Sharjah, in the United Arab Emirates, for a residency that will, one day, be a story I can tell without involuntarily wincing.

The call had been masterminded by Devon Walker-Figueroa, the award-winning poet of Philomath and the forthcoming Lazarus Species, who, at the time, was teaching at Bennington. She had chosen The Eternal Audience Of One as one of the class’s set works and asked me to talk about the novel’s writing process. Devon and I had met about a year before in Windhoek when she was complying with the traveling condition of a scholarship that required her to be out of the US for a year. I was convinced she was on the lam from the law.

Because, really, Windhoek of all places?

Nah, fam. I know a fugitive when I meet one.

Since our meeting, Devon and I shared long and winding conversations about the writing craft, the perils of our chosen literary careers, the hardships of teaching, and the innumerable joys and freedom of reading. When she asked me to speak to her students about my debut novel, I was only too glad. As a bare minimum talking to her students would distract me from my then predicament: a leaking hotel room roof that could never seem to be satisfactorily fixed.

Engaged and switched on, interactive and curious, heartwarming and humorous—that is what I remember of her students. Readers, I have come to realise, are the most meaningful prizes a writer can be given; and to be provided with a room full of eager readers who asked interesting questions about my work remains a moment that I cherish.

And then, about a week later, Devon hit me up and said one of her students—Zuza Gaboush—had done her final year project on The Eternal Audience Of One.

Oh, not just written a paper on it, but made a physical sculpture with a whole abstract.

***

SÉRAPHIN

Zuza Gaboush

The literary source which I used to supplement my creative portion for this final was The Eternal Audience of One, a novel written by Rémy Ngamije. The most striking element of this novel was the main protagonist of this book, Séraphin Turihamwe, and the characterisation of not only his external or “primary” identity, but the additional physical manifestations of his multiple “selves”, symbolizing the multitudinal facets of his being.

To contextualise the meaning behind Séra’s multiplicity of selves, one must acknowledge the historical and religious context behind the name Séraphin. The term “seraphim” originates from Abrahamic religions and defines the existence of celestial beings which are said to protect the Throne of God and guard the Kingdom of Heaven. These beings are typically depicted as creatures containing multiple wings and an abundance of eyes; the latter feature is a distinctive characteristic which grants these angels “ultimate sight”, affording them infinite wisdom and knowledge. These sacred figures are illustrated as repetitious forms, containing a multiplicity of features which generate a sense of the supernatural or an otherworldly existence. Historically, artistic representations of the seraphim depict these angels as six-winged creatures, a numerically significant amount as the six wings refer to the six days it took God to create the earth. These holy beings are all-knowing, eternally faithful, and the ultimate servants.

Séra’s proximity, by name, to these angelic creatures is highly intentional and indicates his multiple versions of self as holy or otherworldly; Séra’s continuous—even obsessive—introspective examination of himself through these selves posits them as holy, or of a higher nature than his individual identity. These characters interrogate Séra’s life choices as if they possess a higher knowledge than Séra himself, often transcending the fictional or metaphysical sphere by forming themselves into physical manifestations of his intangible thoughts.

If Séra can be read as God in this allegory, then his “eternal audience” is fulfilled by his personal seraphims, the multiple versions of himself whose purpose is to dedicate their services to the project of his life. Because these selves are contained within Séra, the “audience” is really just himself, informing the title: The Eternal Audience of One.

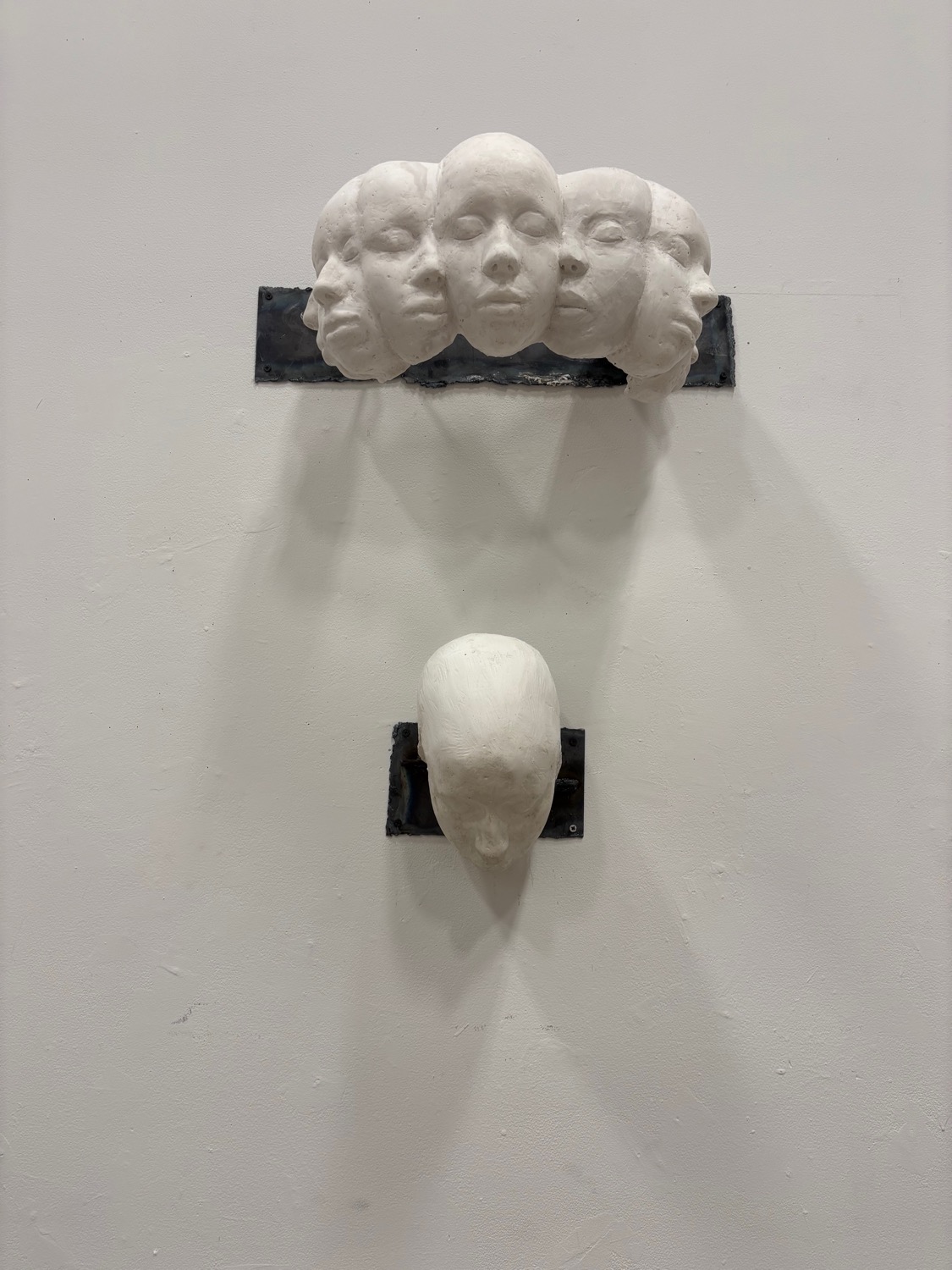

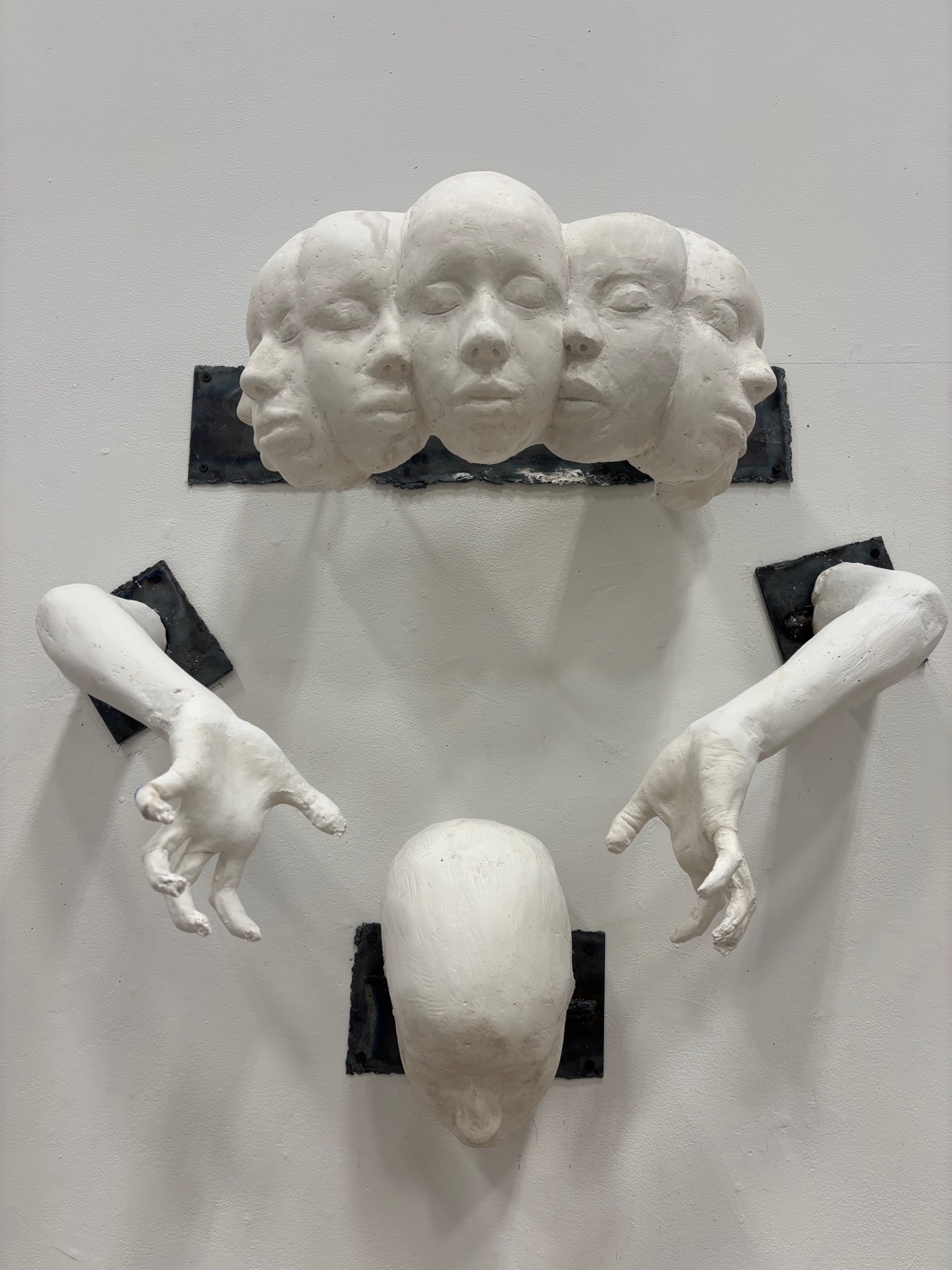

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

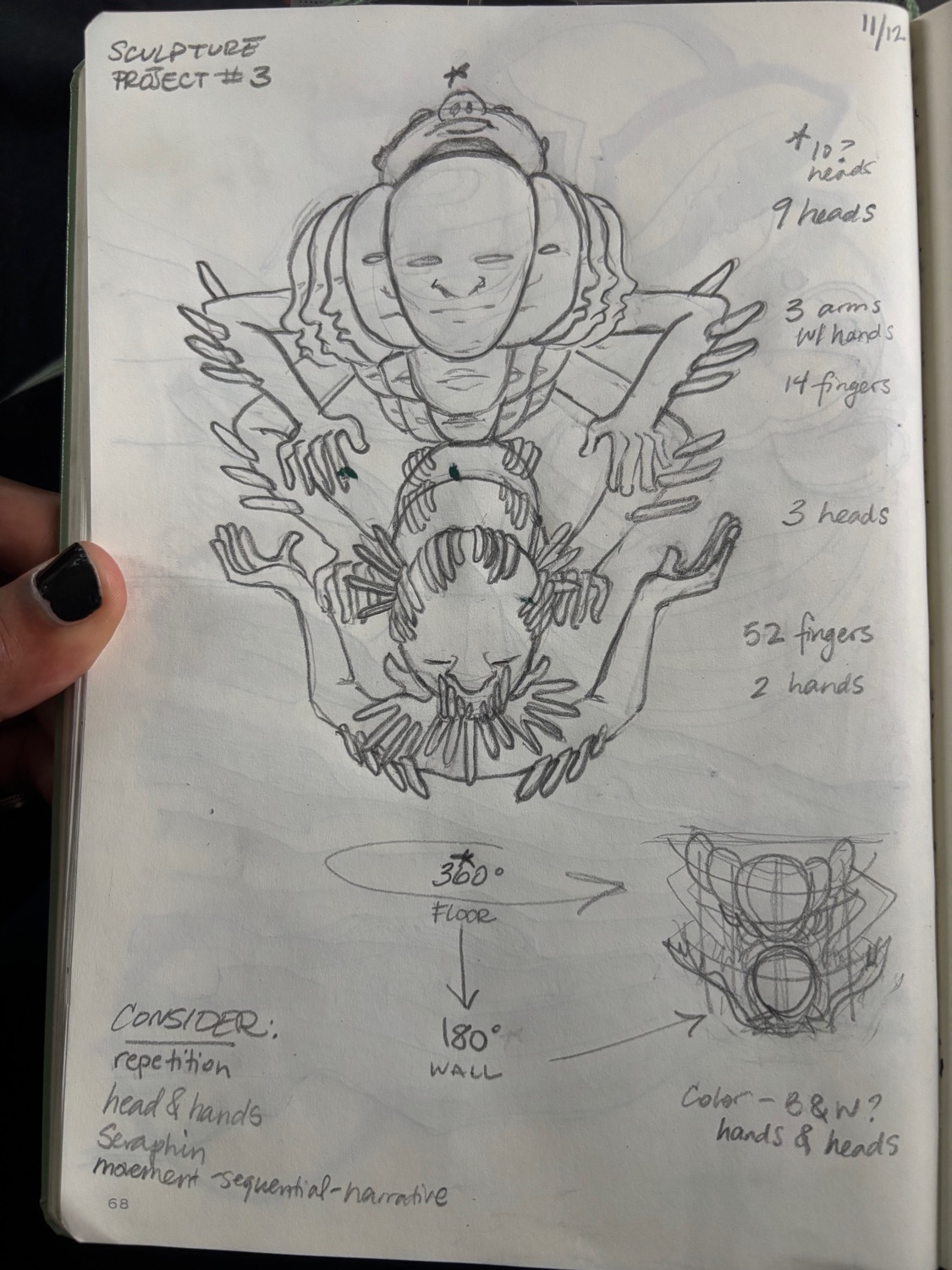

The significance of Séra’s name in the novel is instrumental in my work, as the imagery of the seraphim is what inspired the visual template on which I based this piece on. In a similar format to the physical characterisations of Séra’s internal selves, I aimed to create an external manifestation of these internal selves, constructing these figures out of plaster, wood, and metal.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

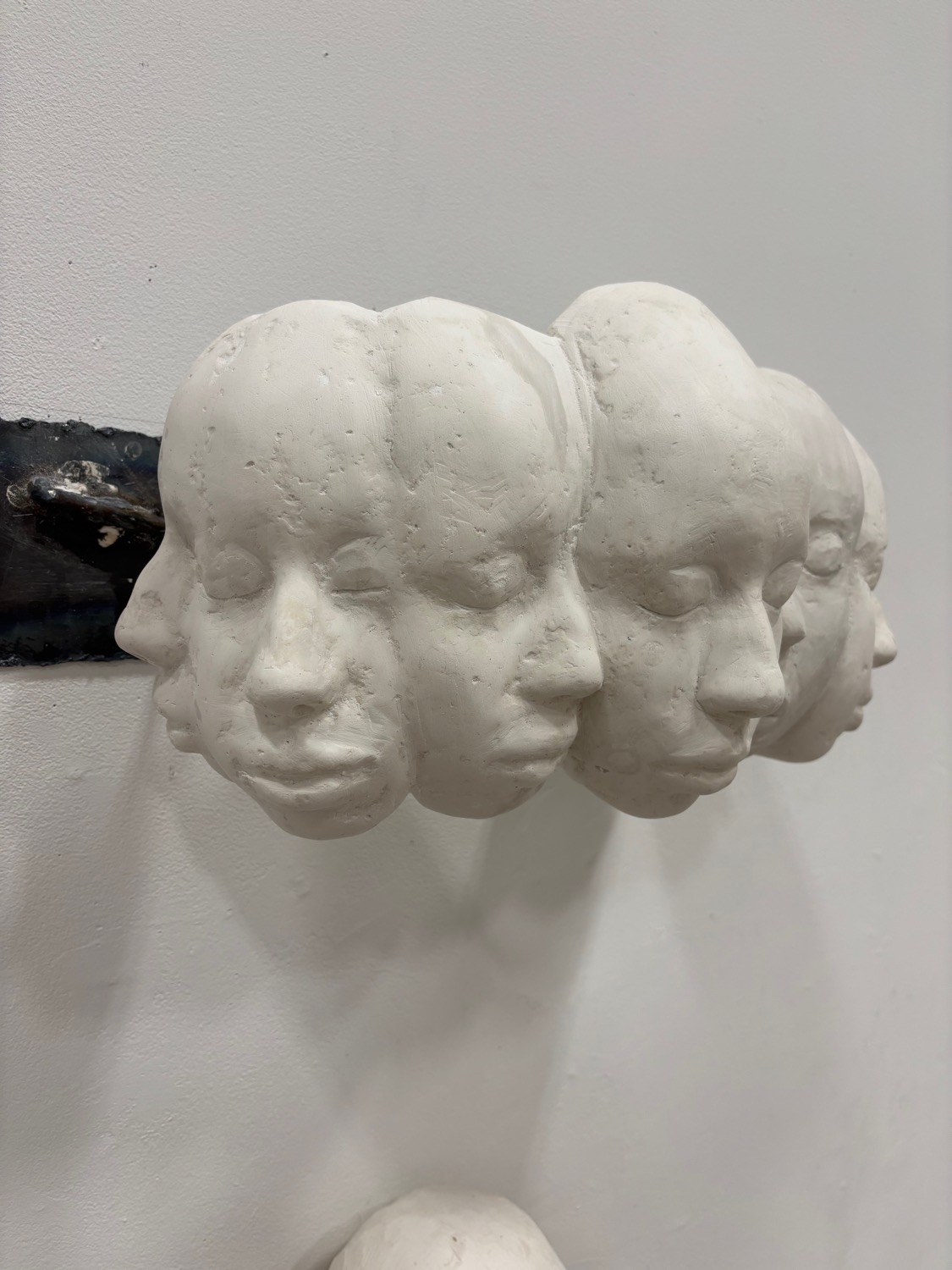

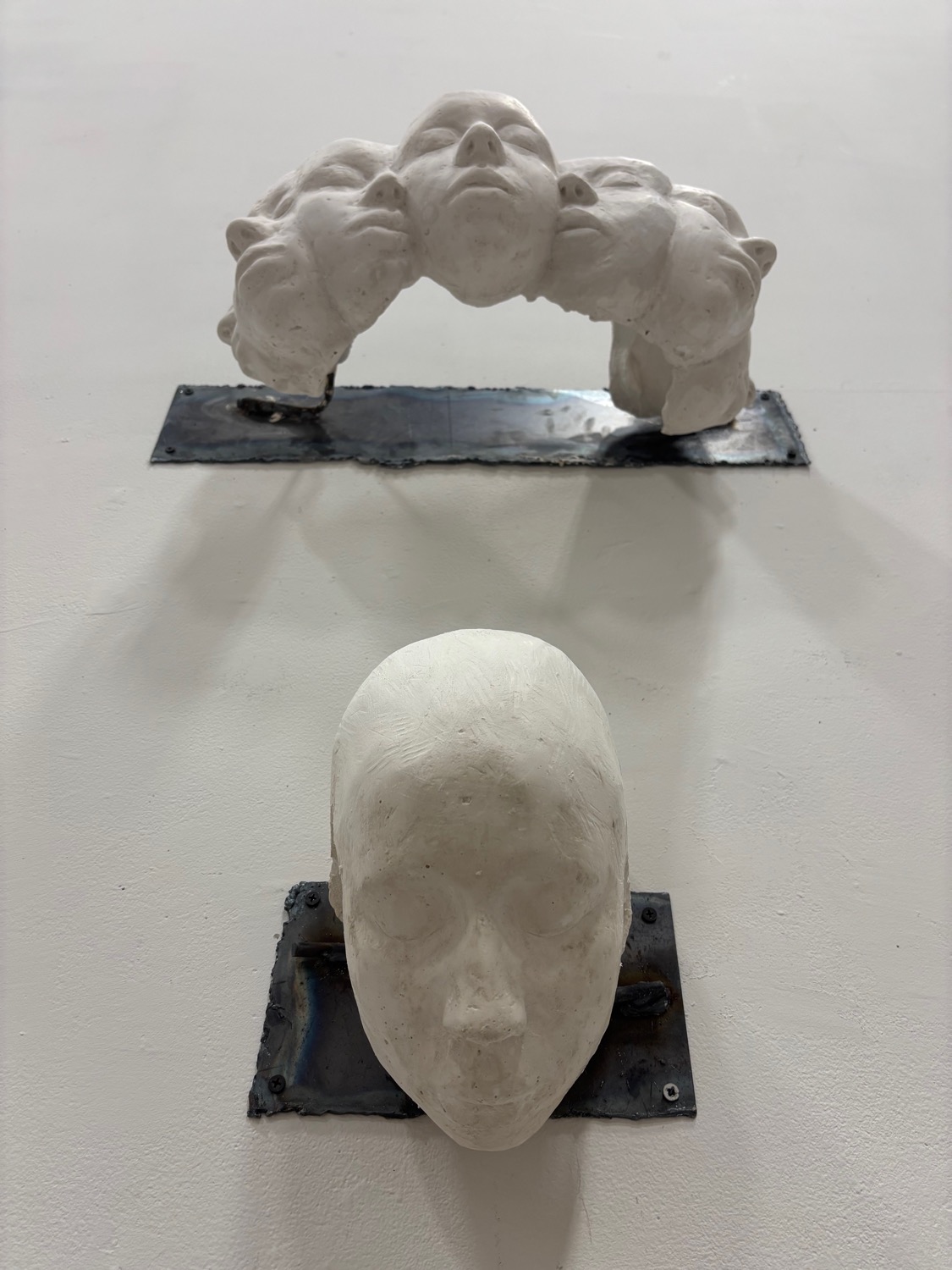

The row of heads that crown the apotheosis of my work represent the seraphims, the constantly aware and observant selves which inform the individual or primary self. The hierarchical dominance of these seven heads in relation to the rest of this piece, as well as the physical world of the viewer lends itself to the omniscient quality of the biblical seraphim, illuminating the power and sacred significance that these selves hold over the individual.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

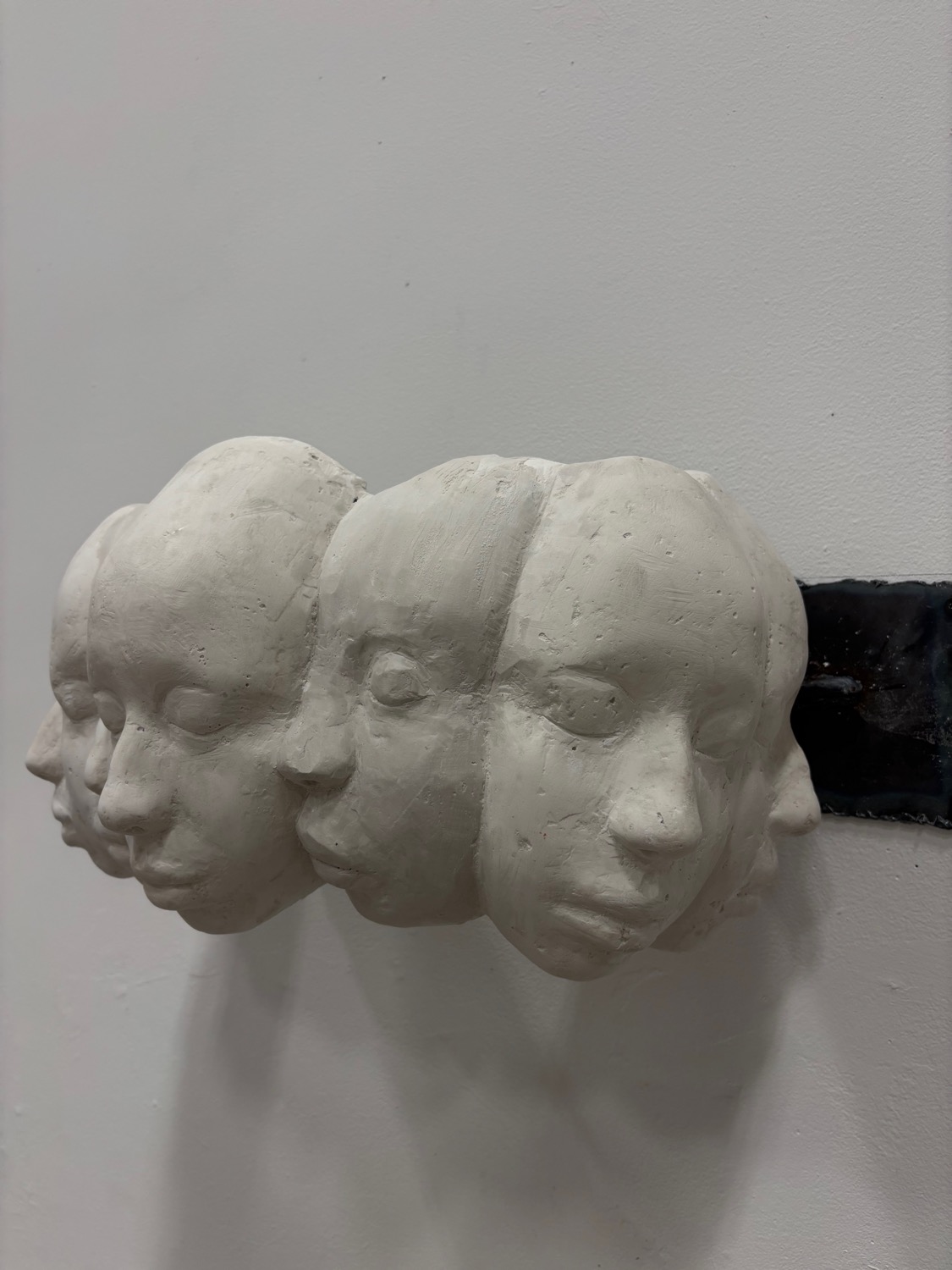

Over seven feet in height from the floor and approximately three feet in length, the seraphim of this piece are designed to loom over the viewer and present themselves as a supernatural entity which inhabits a plane above that of the mortal body. The seventh face in the row, centered between the six adjoining seraphim, is meant to represent the primary self’s intellectual presence alongside its “angels”. The decision to include the primary self in addition to the accompanying selves was taken from the novel’s assertion that, although there is a consistent recurrence of Séra’s selves throughout the story, Séra ultimately remains in charge of his decisions, adhering to the advice of his Great Chamber when he deems it necessary.

The arched form these heads create is central to this idea of authority over self—utilising the shape of an arch—in which the center bears the brunt of the weight. The primary self, the head which faces the world, exists as the integral component which ensures the structural integrity of this entire section, symbolising the literal and metaphorical weight that the intellectual version of the primary self carries in comparison to the assisting selves. This is demonstrated in the novel through Séra’s assertion of autonomy over these selves, ignoring the pressures of not only his seraphim, but the expectations of his family, friends, and cultural values. In this manner, the utmost authority over one’s autonomy is depicted through the centrality of the primary self in my piece, represented as a whole and complete face in contrast to the halved faces of the seraphim.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

The significance of the individual is also represented in the solitary head which is placed underneath the row of seraphim, symbolising the physicality of self—the body whose existence is essential to the conceptualisations performed by the council of selves. Observing this head on a vertical plane, I wanted to illustrate the concept of the physical self bearing the utmost weight of the piece; the council of seraphim and the intellectual version of the individual self cannot exist without the physical body’s presence.

Although the seventh, central head bears the most weight in the context of the council, the physical, embodied representation of the physical self underneath it acts as the grounding cornerstone which supports the upward entirety of this piece.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

Throughout the process of forming this work I was confronted by the sheer physical labour and stamina which was required to execute my vision. This process was heavily embodied—almost violently so—as I had to cut into and chip away at literal copies of myself. I was injured several times, and there were moments where blood was drawn and would spill onto the plaster. To preserve the cohesiveness of this piece, I would have to shave portions of the plaster off to recover the white quality of the material from the stain of my “being there”. The addition of my personal existence, of “invisible” evidence left behind from my bodily labour illustrates my interaction and relationship with the material, and is a theme central to most of my work.

In this context, the intimacy of my physical interaction with this piece is indicative of Ngamije’s belief surrounding the embodied nature present in all artist’s work, specifically in regards to the mirroring of some of his own lived experiences which were consolidated within his novel. Furthermore, the consequential removal of “damaged” elements in the work through an attempt to preserve the “purity” or cohesiveness of this structure can be related to the novel’s themes of survival, as well as its correlating themes of performance and spectacle: “…all the world a stage…” (Ngamije, p 316).

In order to survive his family, friends, and the greater world, Séra is circumstantially forced to give up certain parts of his identity by adhering to others’ expectations. “Home, to him, was a constant source of stress, a place of conformity, foreign family roots trying to burrow into arid Namibian soil which failed to nourish him” (Ngamije, pg. 8) This subtraction of self can be mirrored in the invisibility of damage done to this piece during its creation, illustrating the values upheld in the action of performance; appearing externally unaffected despite the internal turmoil that is suppressed beneath the surface.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

The theme of performance also resonates heavily with the thematic element of silence, another major component of this novel, present in Séra’s behaviour and in his father and mother’s as well. Silence can act as a form of protection, a barrier of detachment that thwarts against possible threats. For Séra, a recurring theme of rejection situates his current state of silence as a response to feeling unwanted, or being refused acceptance based on the facts of his personhood.

This silence is acknowledged by Séra’s teacher in the book, Mr. Caffrey, who notes how Séra’s outward silence has trickled its way into his internal realm as well. “Just the silence, Séra. It shows in your writing too. It’s become, how do you say it, detached. Like you’re studying the world in a petri dish as opposed to being down in the gunk and the ooze of everyday life” (Ngamije, pg. 128).

I chose to depict this theme of silence by depicting a quality of blindness; the eyes on every figure are closed shut, meant to replace a lack of language with a lack of sight—both representative of an intentional removal of agency. In contrast to the biblically accurate seraphim, this intentional removal of eyes lends meaning to the mortality of oneself, juxtaposing the assumed omniscience of the internal selves.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

At the end of the day, Séra is only human, and his constant struggle to survive multiple elements of his life indicates the finite capacity of his physical and mental abilities in contrast to the abilities contained in the seraphim’s metaphysical realm. This quality of blindness can also represent the reader’s experience in understanding the trajectory of Séra’s character, as the non-chronological timeline that structures this narrative effectively separates the reader from a fully comprehensive understanding of Séra’s identity and background. This forces a distance between the reader and the protagonist, evident in my work’s portrayal of blindness as representative of detachment.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

Séraphin. © Zuza Gaboush.

This piece works to physicalise the written description of Séra’s character in The Eternal Audience of One and to emphasise the relationship between the supposed “self” and its supporting facets, all of which amalgamate to subsist as an individual being. This oxymoronic idea of multiples existing as one, cohesive unit is exemplified within the very title that inspired this piece: an audience, but of only one.

***

Allow me to reintroduce her: Zuza ma’fuckin’ Gaboush!

Right, I need to make serious money because I need a Gaboush in my house!

![]()

POSTSCRIPT: Also, your boy got himself two vinyl DJ turntables and is collecting LPs now. Collecting so hard he even drove outside of Windhoek—outside!—to dig through someone’s 400-piece vinyl inheritance in Okahandja. Boney M. (no one asked for your judgment!), The Beatles (gosh, I do not like this band at all, but, hey, resale value), Creedence Clearwater Revival (the rock gods smiled upon me!), John Denver (look, you like what you like), The Mamas & Papas (classic), and Mango Groove (vintage) were just some of the gems I found. So y’all really need to get on the prayer hotline so your boy can make vinyl money. Call me DJ Grammarphone, DJ Heard It Through The Grapevinyl, DJ All Hands On Decks, DJ Needle Drop, DJ Scratch That, or DJ Boulliabass (contributed by my friend Joonas Leskela, an accomplished vinyl collector, but, alas…these savages will not get it). More monikers on the way!

READ: “Young Lover, New Lover” by Muhammad Aladdin (A Public Space) • “Maybe My Most Important Identity Is Being A Son” by Raymond Antrobus (Poetry Foundation) • “We” by Joshua Bennett (Poetry Foundation) • “Inside America’s Death Chambers” by Elizabeth Bruening (The Atlantic) • “Out Of The Fog” by Camille Bromley (The Verge) • “I Can Never Own My Perfect Home” by Lydia C. Buchanan (Electric Lit) • “Books Left On Trains” by Junot Diaz (StoryWorlds) • “How To Make A Living As A Writer” by Gabrielle Drolet (The Walrus) • “Reflections On The 75th Anniversary Of A Nakba That Never Ended” by Mohammed El-Kurd (The Nation) • “Small Poems For Big” by Chinnaka Hodge (Poetry Foundation) • “War, Blossoms” by S. J. Naudé (A Public Space) • “For Scale” by Kevin Nguyen (The Verge) • “Standard” by Som-Mai Nguyen (The Verge) • “Translation Is Where All Languages Meet” by Mukoma Wa Ngugi (The Republic) | WATCH: Andor, season 2 (2025) • Business Insider: How Truck Drivers In India Navigate One Of Of The Most Dangerous Roads In The World (2025) • Bon Appetit: Inside NYC’s Only 3-Star Michelin Korean Restaurant (2025) • Crazy Stupid Podcast: Why Andor Is Such A Masterpiece, Andor’s Deeper Meaning, What America Can Learn From Andor, What Does Luthen Believe In?, Andor Is The Best Star Wars Ever, How Andor Makes Rogue One Better; Sinners: Stop Romantising Segregation; and Squid Game, Season 1 Review: The Violence Of Capitalism (2025) • Mobland, season 1 (2025) • Sinners (2025) • The Agency, season 1 (2024) • The Night Manager, season 1 (2016) • The Last Repair Shop (2024) • Through A Lens Darkly: Black Photographers And The Emergence Of A People (2014) • Turning Point: The Vietnam War (2025) • Your Friends And Neighbors, season 1 (2025) | LISTEN: “Hi-Lo (Hollow)” by Bishop Briggs • “I’m Not Alone” by Calvin Harris • “We Go Down Together” by Dove Cameron featuring Khalid • “One Million Views” (featuring John Mani), “Soundtracks And Comebacks”, and “Washing Over Me” (featuring Morning Parade) by Goldfish • “Here Comes The Hotstepper” by Ini Kamoze • “River Bend” by Hydrologic featuring Surku & At Dawn • “Gaslight” by Inji • “Get You The Moon” by Kina featuring Snøw • “Je Ne Bois Pas Beaucoup” by Les Yas Toupas Du Zaire • “Sing It Back” and “Time Is Now” by Moloko • “The Box” (original and live versions) by Roddy Ricch • “Yamore” by Salif Keïta featuring Cesariá Évora • “Diamond Eyes”, “Love Outside The Lines”, “There’s Nothing Better” (original and remix versions) and “We Are Now” by Shake Shake Go • “Umoya” by Skwatta Kamp featuring Relo • “Sweat” by The All-American Rejects • “Hotel California” by The Eagles • “Your Love” by The Outfield | PLAY: Gotham Knights (2022) | TRY: spending money on the art that really matters.